Author: Dr Damian Harper

(Founder of Human Braking Performance)

The ability to rapidly decelerate horizontal momentum is a critical locomotor skill required for athletes competing in multi-directional sports. In previous blogs I have highlighted the unique force demands associated with intense braking when decelerating rapidly and the implications this can have for performance enhancement, neuromuscular fatigue and injury-risk. One notable unique demand associated with deceleration and braking is the necessity to skilfully generate and attenuate forces throughout the lower limbs (see video 1). This can place substantial force demands on muscles and connective tissues to generate the high internal joint extensor moments required to control joint flexion and to mechanically buffer and absorb energy with minimal damage, which could be caused through fast eccentric muscle action (i.e., active muscle fibre fascicle lengthening/strain). As illustration, when required to decelerate horizontal momentum rapidly, ankle and knee joint flexion velocities can be around 380 and 470 degrees per second, respectively (1).

Video 1. Basketball player braking to perform a rapid horizontal deceleration. Necessitates ability to skilfully generate and attenuate forces throughout the lower limbs!

Given the significance of horizontal deceleration to athletes competing in multi-directional sports, there should be special interest devoted by sports science and medicine practitioners on how to optimally enhance their athlete’s horizontal deceleration ability (i.e., we want to improve our athlete’s ability to perform and be resilient to one of the most mechanically demanding tasks they will be exposed to during competition – deceleration). We have previously highlighted that this could be done by enhancing two key modifiable factors: 1) horizontal deceleration skill and 2) horizontal deceleration specific strength qualities – both of which interact to enhance horizontal deceleration ability (2).

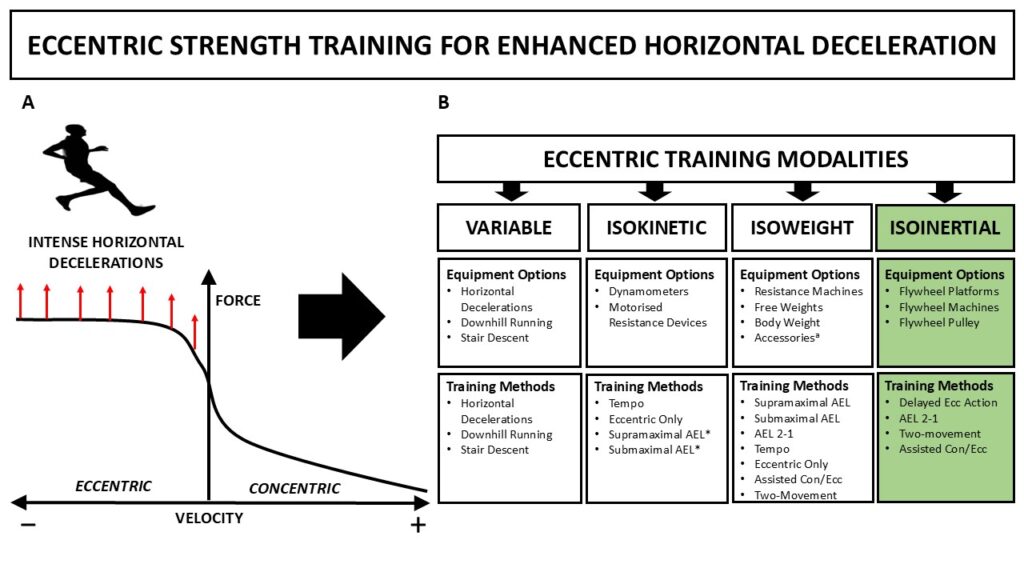

One notable strength quality that is critical for horizontal deceleration is eccentric strength (3). This is primarily due to eccentric strength being associated with the generation and control of joint motions when braking centre of mass momentum (i.e., velocity x mass) in any movement plane, and secondly, due to eccentric muscle actions being capable of generating much higher forces than those observed when performing concentric muscle actions (see Figure 1A). This may explain why athletes are able to generate greater rate of change in velocity when performing horizontal decelerations compared to horizontal accelerations during competitive match play (4), thus enabling them to rapidly reduce their momentum in very short distances and times.

The Role of Flywheel Eccentric Strength Training?

Whilst there are many training modalities and techniques to enhance eccentric strength (Figure 1B), the use of flywheel training devices could be particularly beneficial for enhancing horizontal deceleration and braking capabilities. I first purchased an Exxcentric flywheel training device back in 2016, realising at first hand the unique stimulus that this training modality could provide for enhancing deceleration and braking performance capabilities. An example of this, was the potential to use a flywheel exercise within a warm-up to achieve superior horizontal deceleration performance compared to a warm-up without inclusion of a flywheel exercise (5).

Figure 1. Eccentric strength training for enhanced horizontal deceleration. (A) Force-velocity curve for dynamic eccentric and concentric muscle actions. Intense horizontal decelerations demand high eccentric strength capabilities across a range of eccentric velocities. Red arrows indicate need to increase eccentric force across a range of eccentric velocities to enhance horizontal deceleration ability. (B) Eccentric strength training modalities that can be used to enhance horizontal deceleration with equipment options and training methods. Adapted from Franchi & Maffiuletti (6).

Specifically, when using a flywheel training device, inertia generated in the concentric propulsive phase of the movement must be subsequently decelerated with a high braking action during the eccentric phase on every repetition of the set (7). This is not possible with traditional (isoweight) resistance training, where muscle activation is submaximal throughout the entire eccentric phase of a set, and up to the “sticking-point” during the concentric phase of a set (8). Therefore, traditional resistance training can be prone to ‘underloading’ the eccentric braking phase (9), which is not favourable for developing the braking and eccentric strength qualities required to rapidly decelerate horizontal momentum, such as when ‘pressing’ and changing direction repeatedly in multi-directional sports!

Traditional resistance training can be prone to ‘underloading’ the eccentric braking phase, which is not favourable for developing the braking and eccentric strength qualities required to rapidly decelerate horizontal momentum, such as when ‘pressing’ and changing direction repeatedly in multi-directional sports!

This is in agreement with professional soccer practitioners, where there is a high consensus that when flywheel training is implemented regularly into soccer training regimes it can have a profound effect on enhancing a player’s change of direction (COD) performance capabilities (10). These perceptions are also evident in experimental data, where just one session per week of flywheel parallel squats (inertia: 0.11 kg.ms-2) performed over a 10-week period elicited significantly greater increases (effect size = moderate-to-large) in COD speed performance in comparison to a group who performed the same exercise with a traditional loading approach (i.e., 80% 1-RM) alongside routine soccer specific training (11). Interestingly, the flywheel training group had greater increases in eccentric quadriceps peak torque, whereas the traditional group had greater increases in concentric quadriceps peak torque, demonstrating adaptations specific to the training stimulus. Therefore, the authors concluded that training with flywheel squats likely led to greater braking abilities which transferred to enhanced deceleration and COD speed performance (see Videos 2-4).

Indeed, systematic reviews examining the use of flywheel training all highlight beneficial responses of flywheel training on COD performance for athletes competing in multi-directional sports, with these findings further summarised in an umbrella review on the topic (12). Therefore, flywheel training seems a particularly effective training modality for facilitating enhanced eccentric braking capabilities that transfer to enhanced horizontal deceleration and COD performance.

Videos 2-4. Hand supported squat variations (parallel, split, and rear foot elevated) performed on the kBox Pro by Exxentric demonstrated by Chris Cervantes, Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach of the Houston Texans American football team. Hand supported squat variations provide greater stability, but also allow the athlete to use an assisted concentric action that generates greater inertia into the eccentric (downward) phase, requiring higher braking forces to decelerate the inertia of the flywheel.

Choosing Flywheel Exercises to Enhance Horizontal Deceleration Ability?

Another clear advantage of flywheel training is the option to generate eccentric braking force demands in all movement planes (i.e., vertical, horizontal and rotational) through use of flywheel platforms and pulley devices. A number of studies have reported superiority of horizontal unilateral flywheel (e.g., kPulley) when compared to bilateral vertical flywheel exercises on various COD performance tests (13, 14). Similarly, whilst flywheel bilateral squats have been observed to have a post activation performance enhancement (PAPE) effect on kinetic parameters in the vertical countermovement jump, the PAPE effect on kinetic parameters in the horizontal plane required to facilitate faster deceleration and COD performance may not be as effective (15). Therefore, for the purposes of promoting enhanced braking ability in each limb, and to help avoid potential inter-limb braking asymmetries, unilateral horizontal flywheel training should help to facilitate rapid deceleration and COD performance from both limbs, which might not be achieved when using solely bilateral vertical flywheel exercises (14).

Flywheel knee extension or flexion machines or combinations of the two (e.g., SingleExx) can also permit targeted unilateral eccentric overload training, which could be particularly important given the associations between unilateral eccentric quadriceps and hamstring strength capacities and maximal horizontal deceleration abilities (3). Indeed, flywheel leg extension exercise has been reported to be superior to constant load for increasing eccentric quadriceps and hamstring muscle activation (8, 16, 17). Accordingly, the greater mechanical tension generated with flywheel single-joint exercises can result in superior quadriceps muscle size and strength compared to traditional constant load exercise following a short 5-week training period (8, 16). Furthermore, multi-joint flywheel exercises, like the squat, may lead to inferior activation of important braking muscles such as the rectus femoris and hamstrings (18). Therefore, using single-joint flywheel exercises to target eccentric strength development of muscles known to contribute to braking and braking force attenuation seem important inclusions alongside flywheel multi-joint vertical and horizontal orientated exercises.

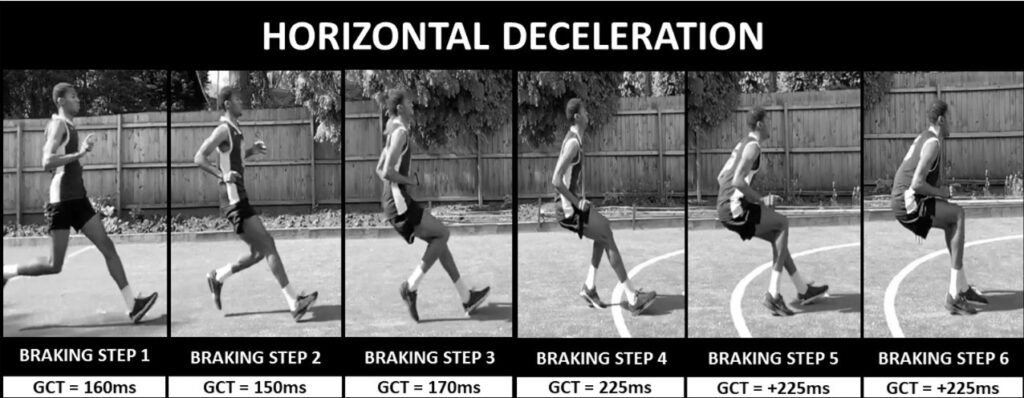

A further important consideration when selecting flywheel exercises is to carefully examine the demands (i.e., spatiotemporal, joint kinematics, body positions) of different braking steps when decelerating from different whole body movement velocities. Figure 2 is a kinogram illustrating sequence of braking steps (x6) during a maximal horizontal deceleration performed from high sprinting speed.

Figure 2. Kinogram illustrating sequence of braking steps during a maximal horizontal deceleration performed from high sprinting speed.

As can be seen in figure 2 the earlier braking steps have shorter ground contact times (i.e., ~150-170 ms) than those in the later deceleration phase (i.e., ~225+ ms), demanding braking to be generated with single limb support and with less joint flexion angles. This has some important considerations for selecting flywheel exercises and programming variables (i.e., sets, reps, load, range of movement) that may best transfer to improved horizontal deceleration performance. For example, flywheel exercises prescribed with single limb support, lower inertial loads and with partial ranges of movement may best develop the qualities needed to brake quickly in the early deceleration phase, whereas those in the late deceleration phase may be best developed with double limb support, a variety of inertial loads and across greater ranges of movement. This has important implications for athletes competing in different sports, where decelerations may be performed from a wide range of speeds (e.g., soccer), or in some sports where decelerations may be predominantly performed from lower speeds (e.g., basketball). As such, practitioners should carefully consider the deceleration demands of the sport and position and prescribe flywheel exercises that may be best conducive to these demands.

Practioners should carefully consider the demands of the sport and position and prescribe flywheel exercises that may be best conducive to these demands.

Practitioner Guidelines for Prescribing Flywheel Exercises?

Table 1 provides a summary of practitioner guidelines for programming (19) and periodizing (20) flywheel training into pre-season or in-season periods for athletes competing in multi-directional speed sports. Future research is required to investigate the influence of different flywheel exercises and programming variables on an athlete’s horizontal deceleration and braking performance capabilities, since research to-date has only investigated the influence of flywheel training on overall COD performance times, or the forces generated in the final foot contact of a COD manoeuvre. Given the increased braking demands of athletes competing in multi-directional speed sports, training interventions like flywheel training alongside other braking performance exercises (21), will likely help to ensure athletes develop the braking performance capabilities required to perform rapid decelerations and COD manoeuvres and to mitigate injury-risks associated with intense decelerations.

Table 1. Evidence-based guidelines for programming and periodising flywheel eccentric training.

Programming Variables | Guidelines |

Training Intensity | · Range of inertial settings (0.025 to 0.11 kg/m2) required to target various eccentric-braking force and power capacities · Higher inertial intensities (> 0.05 kg/m2) may be preferable for eccentric-braking strength adaptations · Lower inertial intensities (i.e., 0.025 to 0.05 kg/m2) may be preferable for eccentric-braking power adaptations |

Training Volume | · Between 3 to 6 sets · Between 6 to 8 repetitions |

Rest Intervals | · Higher inertial loads require longer rest periods (i.e., > 2 mins) · Lower inertial loads require shorter rest periods (i.e., < 2 mins) |

Training Frequency & Duration | · 2 to 3 sessions per week · 5 to 10 weeks

Note: 1) Positive effects on COD have been reported using just one session per week in-season, 2) Early functional and morphological adaptations have been reported following short-term (4-week) squat protocols (5 sets of 10 repetitions) |

Considerations for periodisation | · Pre-season or periods with single competitive game: Two sessions per week. First session on MD-4 should focus on injury prevention and eccentric-braking strength development, while the second session (MD-2) should have a focus on eccentric-braking power development with lower inertial loads and overall volume (i.e., combination of sets and reps) · In-season periods with one competitive game: 1) Starters (i.e., players who played high minutes of competitive game) could perform two sessions per week. First session on MD-4 could focus on injury prevention and eccentric-braking strength development, with second session on MD-2 focusing on eccentric-braking power using a micro-dosing scheme (i.e., low volume and high-intensity, e.g., 1-2 sets, 2-3 exercises) with low inertial loads. 2) Non-starters (i.e., substitute players with lower game time) could perform three sessions per week. First session on MD+2 could focus on injury prevention and eccentric-braking strength development, second session on MD-4 could focus on eccentric-braking power development with third session using a micro-dosing scheme · In-season periods with two competitive games (i.e., fixture congestion): One session per week on MD-2 focusing on eccentric-braking power development with option to implement a micro-dosing scheme on MD-2 prior to the second match |

MD-4 = Four days prior to competitive game, MD-2 = Two days prior to competitive game, MD+2 = Two days following a competitive game, COD = Change of direction | |

Key Take Home Points...

-

Deceleration demands athletes to be able to generate and attenuate high braking forces. Eccentric training approaches, like flywheel eccentric strength training, can facilitate enhanced braking capabilities that transfer to enhanced horizontal deceleration and COD performance.

-

Unilateral horizontal flywheel training can help to facilitate rapid deceleration and COD performance from both limbs, which might not be achieved when using solely bilateral vertical flywheel exercises. Practitioners should therefore look to use a combination of flywheel devices and exercises to develop well rounded braking capabilities.

-

The evolution and future evolution of multi-directional speed sports is demanding athletes to generate and tolerate high braking forces, repeatedly. Practitioners should place special focus on training approaches that can help enhance athlete’s deceleration and braking performance capabilities.

Dr Damian Harper

Damian is the founder of Human Braking Performance. He has consulted with many high-performance organisations and technology companies around the assessment and training of horizontal deceleration and braking performance. For enquiries around consultancy, individual or group CPD please enquire through the Human Braking Performance website here.

Follow @DHmov @BrakingPerform

References

1. Jordan AR, Carson HJ, Wilkie B, Harper DJ. Validity of an inertial measurement unit system to assess lower-limb kinematics during a maximal linear deceleration. Cent Eur J Sport Sci Med. 2021;33(1):5–16.

2. Harper DJ, Kiely J. Damaging nature of decelerations: Do we adequately prepare players? BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4:e000379.

3. Harper DJ, McBurnie AJ, Santos TD, Eriksrud O, Evans M, Cohen DD, et al. Biomechanical and neuromuscular performance requirements of horizontal deceleration: A review with implications for random intermittent multi-directional sports. Sport Med. 2022 29;52(10):2321–54.

4. Oliva-Lozano JM, Fortes V, Krustrup P, Muyor JM. Acceleration and sprint profiles of professional male football players in relation to playing position. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):

5. Waite L, Harper D. The potentiating effects of flywheel eccentric overload on sprint acceleration and deceleration performance. In: British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences Student Conference 2018 Northumbria University, UK. 2018.

6. Franchi M V., Maffiuletti NA. Distinct modalities of eccentric exercise: Different recipes, not the same dish. J Appl Physiol. 2019;127(3):881–3.

7. Raya-González J, Castillo D, Beato M. The flywheel paradigm in team sports: A soccer approach. Strength Cond J. 2021. 43(1):12–22.

8. Norrbrand L, Pozzo M, Tesch P a. Flywheel resistance training calls for greater eccentric muscle activation than weight training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110:997–1005.

9. Quinlan JI, Narici M V, Reeves ND, Franchi M V. Tendon adaptations to eccentric exercise and the implications for older adults. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2019;4(3):60.

10. de Keijzer KL, McErlain-Naylor SA, Brownlee TE, Raya-González J, Beato M. Perception and application of flywheel training by professional soccer practitioners. Biol Sport. 2022;39(4):809–17.

11. Coratella G, Beato M, Cè E, Scurati R, Milanese C, Schena F, et al. Effects of in-season enhanced negative work-based vs traditional weight training on change of direction and hamstrings-to-quadriceps ratio in soccer players. Biol Sport. 2019;36(3):241–8.

12. de Keijzer KL, Gonzalez JR, Beato M. The effect of flywheel training on strength and physical capacities in sporting and healthy populations: An umbrella review. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022;17(2):1–18.

13. Gonzalo-Skok O, Tous-Fajardo J, Valero-Campo C, Berzosa C, Bataller AV, Arjol-Serrano JL, et al. Eccentric overload training in team-sports functional performance: Constant bilateral vertical vs. variable unilateral multidirectional movements. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016. 14;12(7):951–8.

14. Núñez FJ, Santalla A, Carrasquila I, Asian JA, Reina JI, Suarez-Arrones LJ. The effects of unilateral and bilateral eccentric overload training on hypertrophy, muscle power and COD performance, and its determinants, in team sport players. Sampaio J, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018. 28;13(3):e0193841.

15. McErlain Naylor SA, Beato M. Post flywheel squat potentiation of vertical and horizontal ground reaction force parameters during jumps and changes of direction. Sports. 2021;9(1).

16. Norrbrand L, Fluckey JD, Pozzo M, Tesch P a. Resistance training using eccentric overload induces early adaptations in skeletal muscle size. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;102(3):271–81.

17. Tous-Fajardo J, Maldonado RA, Quintana JM, Pozzo M, Tesch PA. The flywheel leg-curl machine: offering eccentric overload for hamstring development. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2006;1(3):293–8.

18. Illera-Domínguez V, Nuell S, Carmona G, Padullés JM, Padullés X, Lloret M, et al. Early functional and morphological muscle adaptations during short-term inertial-squat training. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1–12.

19. Beato M, Dello Iacono A. Implementing flywheel (isoinertial) exercise in strength training: Current evidence, practical recommendations, and future directions. Front Physiol. 2020; 11:1–6.

20. Beato M, Maroto-Izquierdo S, Hernández-Davó JL, Raya-González J. Flywheel training periodization in team sports. Front Physiol. 2021;12:1–6.

21. Harper DJ, Cervantes C, Van Dyke M, Evans M, McBurnie A, Dos’ Santos T, et al. The Braking Performance Framework: Practical recommendations and guidelines to enhance horizontal deceleration ability in multi-directional sports. Int J Strength Cond [Internet]. 2024, 13;4(1):1–31.